The sights and smells of your first doctor visits make quite an impression. That was the case with my pediatrician, Dr. Kingsley. In the waiting room was a jolly plastic rocking horse, with exposed springs, that nowadays might require your signature on a release form shielding the practice from liability. The smell of alcohol permeated the office, either because of the acuteness of my young senses, or because alcohol was the go-to for disinfecting glass thermometers. There was the sound of the rubber squeeze bulb while your blood pressure was being taken, and the ice-cold stethoscope pressed against your delicate skin.

Dr. Kingsley, clad in a long white lab coat, would always be putting out a cigarette as he entered the room. Doctors, like everyone else at the time, had been sold on the idea of cigarettes being responsible for any number of positive health benefits. In fact, television and magazine ads celebrated surveys showing that doctors as a profession had a favorite: Camels! The cigarette that had no filters!

I think comedian Chris Parnell had Dr. Kingsley in mind when performing his 30 Rock role as Dr. Leo Spaceman: "If your mother smoked Chattertons, your sexual organs are covered in bone."

Dr. Kingsley’s opening gambit was to ask what you had for breakfast, perhaps as a way of distracting you from the prick of the lancet pen he pressed against your index finger. The tiny blood spot, dabbed onto a special paper strip, would be slid along a scale with different shades of red. He’d eyeball the color of your blood against these samples—the darker the red, the better—before passing judgment.

As he slid your blood spot up the scale, he’d narrate your progress, much as the chemist-for-hire did while evaluating the white powder in The French Connection — “Lift-off… lunar trajectory… grade-A poison…” — only in this case, the scale was, “French fries… hot dogs… steak…” I suppose making the connection between diet and health wasn’t wrong, but really, the tool was about as accurate as a slide rule covered in ketchup.

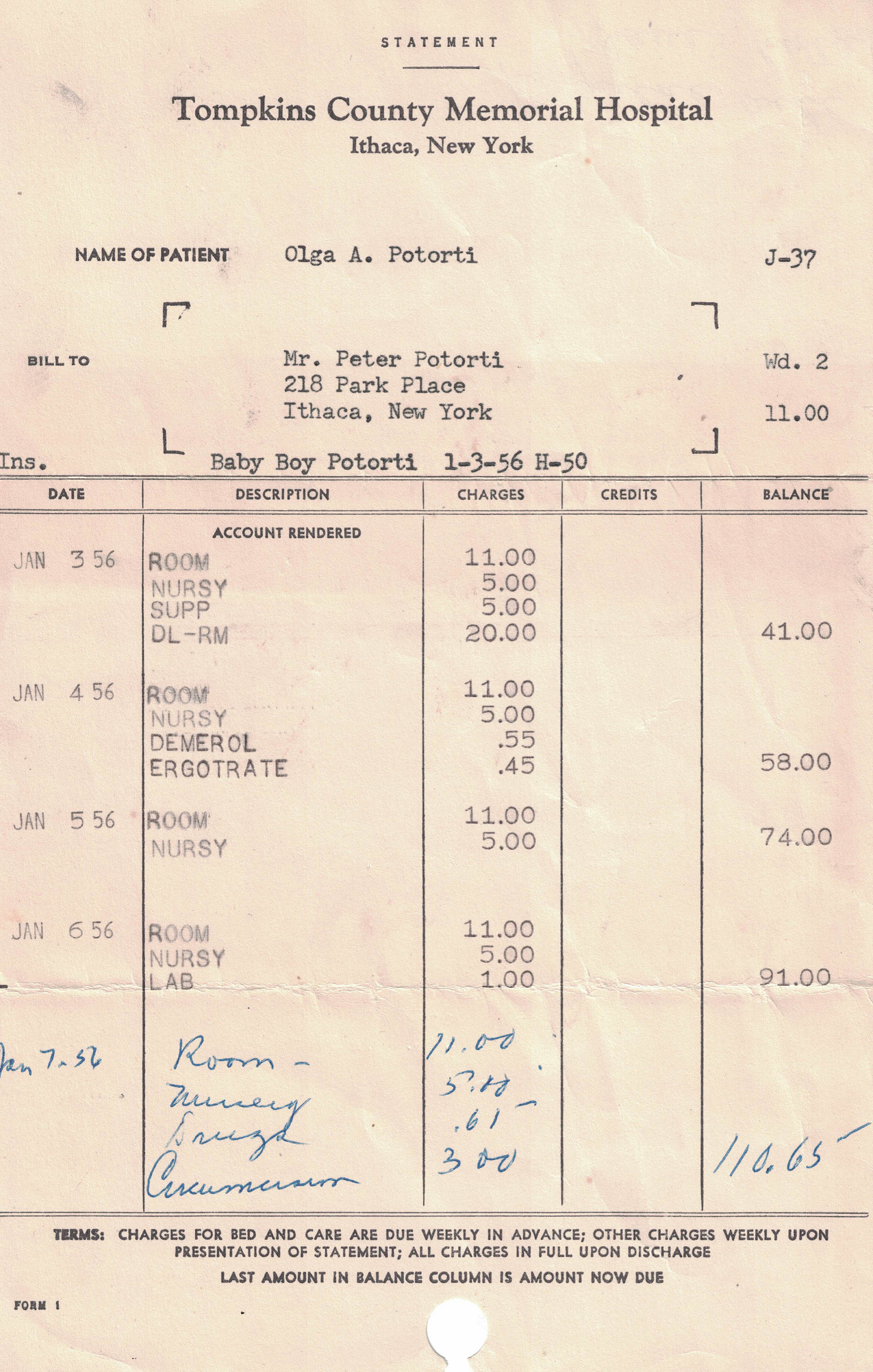

It cost $110.65 for me to be born. The bill from Tompkins County Memorial Hospital, addressed solely to my father, referred to “Baby Boy Potorti,” which could have been my Championship Wrestling name. My mom’s hospital stay lasted from January 3rd through January 7th, five days, for an ordinary delivery with no complications. The room was $11/day, and the delivery room was $20. Mom got Demerol, an opiate, during her delivery for 55 cents, and Ergotrate, which had something to do with reducing bleeding, for 45 cents.

My circumcision required a payment of $3.00. Associated drugs were 61 cents. Wouldn’t want to cut corners there.

Those were the days of real miracles in medicine, many of them involving needles. There was the smallpox vaccine, which involved surrendering your left arm to 15 pricks in a circle. Then there was the experimental, killed-virus polio vaccine created by Jonas Salk, who in 1953 was kind enough to test it on himself and his family—thanks Honey!—before sending it out to 1.6 million children in Canada, Finland and the USA. Between 1957 and 1961, annual cases of smallpox dropped from 58,000 to 161.

Today, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) notes Salk’s commitment to equitable access to his vaccine, and his championing of universal, low- or no-cost vaccination in order to thoroughly eliminate the disease. He didn’t profit from sharing his vaccine with six pharmaceutical companies, and when asked who owned the patent, famously replied, “Well, the people, I would say. There is no patent. Could you patent the sun?”

Salk’s refreshing altruism around vaccines is nowhere to be seen today. Apparently those 15 pricks in a circle are now the CEOs of pharmaceutical companies.

Dr. Sabin administers his liquid polio vaccine. I guess he ran out of sugar cubes. Credit: WHO/Pasteur Meriuex

Albert Sabin’s oral polio vaccine followed. It used a live, weakened form of the virus but was a lot easier to administer, frequently in liquid form on a sugar cube. I remember lining up in my grade school library and solemnly receiving my sugar cube like a kind of Communion wafer.

There were mumps, measles, and chicken pox, which were accepted rites of passage for kids. While some enjoy chicken pot pies, I’ve heard of people having chicken pox parties, where a play date was arranged with the first child to get infected so that all the neighbor kids could get infected at the same time and get it over with. This was before they invented a vaccine. And, apparently, lawyers.

Doctors went the extra mile in those days, enjoying long relationships with the family. One Christmas Eve, I slipped and split my chin on a wooden desk, requiring a stitch. It was dark and snowing when we called family physician Dr. Galvin, whose office was two blocks away. He met us there, administered some penicillin powder and closed the wound. I still have the scar.

On another Christmas Eve, I was diagnosed with walking pneumonia. And on still another, I had a tooth extracted, and wound up on the couch with a bottle of Darvon, an opiate painkiller created in 1955. In 1978, the consumer group Public Citizen petitioned the government to pull it off the shelves due to its propensity for causing heart problems. It was withdrawn 32 years later, in 2010. I guess the FDA wanted to make extra sure that none of those CEOs would get hurt.

Nowadays, Christmas Eve visits are limited to urgent care facilities and emergency rooms. You won’t get a sugar cube, and you won’t know the doctor. But hopefully he or she won’t be smoking Camels.

© 2022 David Potorti

Your writing is so good and so funny David.

This one really had me chuckling!