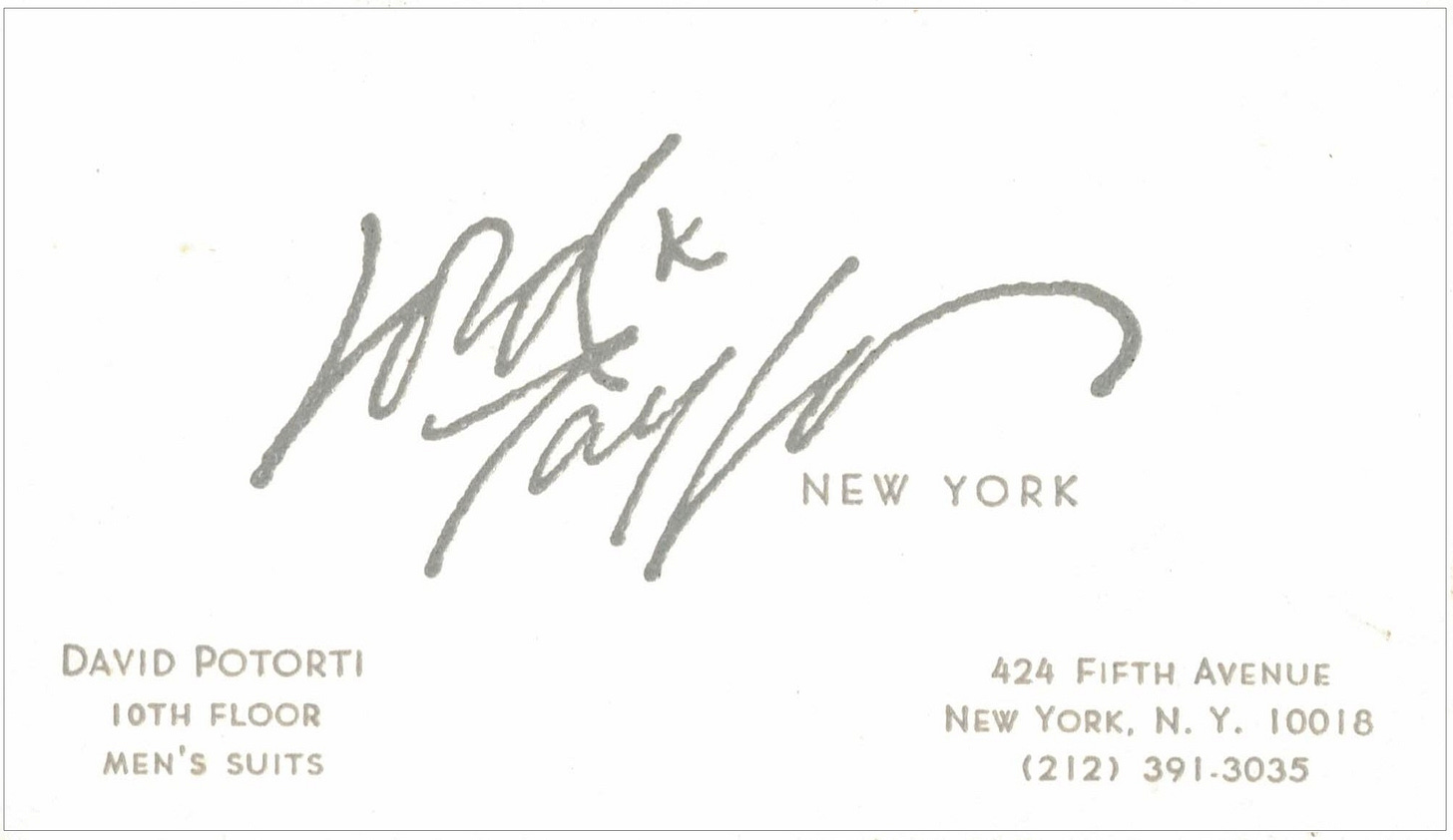

Some wait tables. Others work retail. While David Sedaris was launching his career as an elf at Macy’s, I was waiting on drunks at Lord & Taylor, the department store in Manhattan.

It was my first subsistence job in New York City, at the flagship store on Fifth Avenue dating back to 1914. The customers weren’t always drunks; just on St. Patrick’s Day, when they’d peel off the famous parade that passed by the front of the store, go wandering past the Clinique section and take a manned elevator to the 10th floor. Somehow they got through, never quite lucid enough to know why they were there or what they were looking for.

The big department store era was still going strong in the 1980s, with B. Altman a few blocks away, and Macy’s and Gimbel’s an avenue over on Herald Square. They were swell affairs with polished wood fixtures and stunning displays. They had fancy restaurants with fare like she-crab soup so you could lunch without leaving the store. And they sold hats that would go into square cardboard boxes with roses on them. My girlfriend patronized the boys department at Lord & Taylor because the clothes cost half as much as the women’s versions.

I had a great British boss who navigated the personality quirks of the young hires and the older generation of commissioned salespeople. There was a German scold who gave her junior coworkers a hard time for not following directions. She got punked when one of them secreted a dozen electronic theft devices throughout her winter coat and watched her get seized by security for setting off the alarm at the exit. They’d remove a security device and she’d set off the alarm again, prompting another search. And another.

In fact, there was lots of “shrinkage.” According to a training video at the time, employee theft added up to losses of $1 million a year at that flagship store alone. The professional shoplifters had our number, too, even if we could spot them a mile away. They’d show up about 15 minutes before closing, when the salespeople were distracted while counting money to close out their registers. They’d wear full-length coats and hang a dozen pairs of jeans inside. You’d find anti-theft devices on the floor of the dressing room, probably removed with a stolen anti-theft device remover. Once in a while one of the old salesmen would leap over a counter in pursuit, but there was no upside to that kind of heroics.

Are You Being Served?

The department store was a great setting for comedy, as demonstrated in TV shows like the innuendo-laden Britcom Are You Being Served? and movies from Miracle on 34th Street to Elf. In the home furnishings department, I was chatting with a colleague next to a pyramid of glass display cubes. I handled some sort of decorative platter on the top shelf and it fell, crashing through the glass and setting off a domino effect that shattered every cube in the stack, raising a pandemonium that froze every customer in silence. I remember my friend waving me off, as if to say, “save yourself.”

Buzz commandeers the elevator in The Hudsucker Proxy

And they had appurtenances you rarely see any more, like elevator attendants. They’d perch on a tiny round stool, open and close an accordion screen, and pull on a big handle to get moving. They’d exhibit real talent in lining up the floor of the car with the floor of the store so no one went tumbling down the elevator shaft.

Still, there were the close quarters, the perfume, the bags, and the boxes. And always, the going up and down. Piloting your scow on a swelling sea of humanity could not have been fun.

I spent enough time in men’s suits to correctly guess your size like a carnival barker. But there were challenges. A South American with a thick accent asked for an acapone suit. Alpaca? No, acapone. After an exchange of hand gestures, I determined that he wanted an Al Capone suit—the navy blue kind, with pinstripes.

I was familiar with kosher food, but not with kosher clothing, and got schooled when a Hasidic man arrived with his Rabbi in search of a tuxedo. The Rabbi was on hand to perform a shatnez test, which made our in-store tailor, an Italian, roll his eyes.

Credit: sewjewish.com

The test policed the biblical prohibition against wearing wool and linen sewn together in the same garment (see Deuteronomy 22:11), although wearing a wool skirt and a linen blouse was okay because they weren’t commingling.

Who knew that clothes could be dangerous? The worst thing that happened during my stint on the 10th floor was developing a callous on the side of my hand from sliding it in and out of the scratchy wool suits on hangers.

The tailor was vexed because the shatnez test involved cutting open the jacket to see if it passed muster. The issue was of keen interest to the Shomer Shabbos, the observant Jews who followed the rules, like Walter, the testy Vietnam vet and divorced Jewish convert in The Big Lebowski:

The shatnez rule is known as a chok, a law that cannot be explained— sort of like Canada’s tax exemption for breakfast cereals that contain toys, as long as the toys aren’t beer, liquor or wine. I suppose just about every faith has them, although most don’t require a seam ripper.

At least the Amish know why they can’t use zippers—they’re ostentatious!

And that would be a sin.

© 2022 David Potorti

This is great…and in so many ways!

Love the characters of life and how you bring them to life on the "page." Also loved the irony in "stolen anti-theft device remover." LOL.