The Price is Right

"These people have taken leave of their senses"

Did you know that Imperial Margarine is unconditionally guaranteed to taste like the 70-cent spread, yet costs so much less?

That would have been useful knowledge if you watched The Price is Right during its original run between 1956 and 1965, with host Bill Cullen and announcer Don Pardo. Today, it’s just hard to believe that a pound of butter used to cost 70 cents.

I’m too young to have more than a dim recollection of the program on my parents’ black and white television set, where it was part of the game show ecosystem occupied by What’s My Line, I’ve Got a Secret, To Tell the Truth, and Concentration. Without the bells and whistles of modern television, it was the contestants, and their weird occupations, funny last names and accents that made these shows entertaining.

Broadcasting out of New York City, sophisticated panelists might wear evening gowns, and guests might wear suits. As shows moved to the West coast and baby boomers came of age, shows reflected the changing culture. When I pull up a rerun of Match Game ‘73, The Dating Game or The Newlywed Game, it’s the clothes I enjoy most—the foot-wide lapels, the bell bottoms, the muttonchops and the bright colors. Yes, these people once roamed the earth.

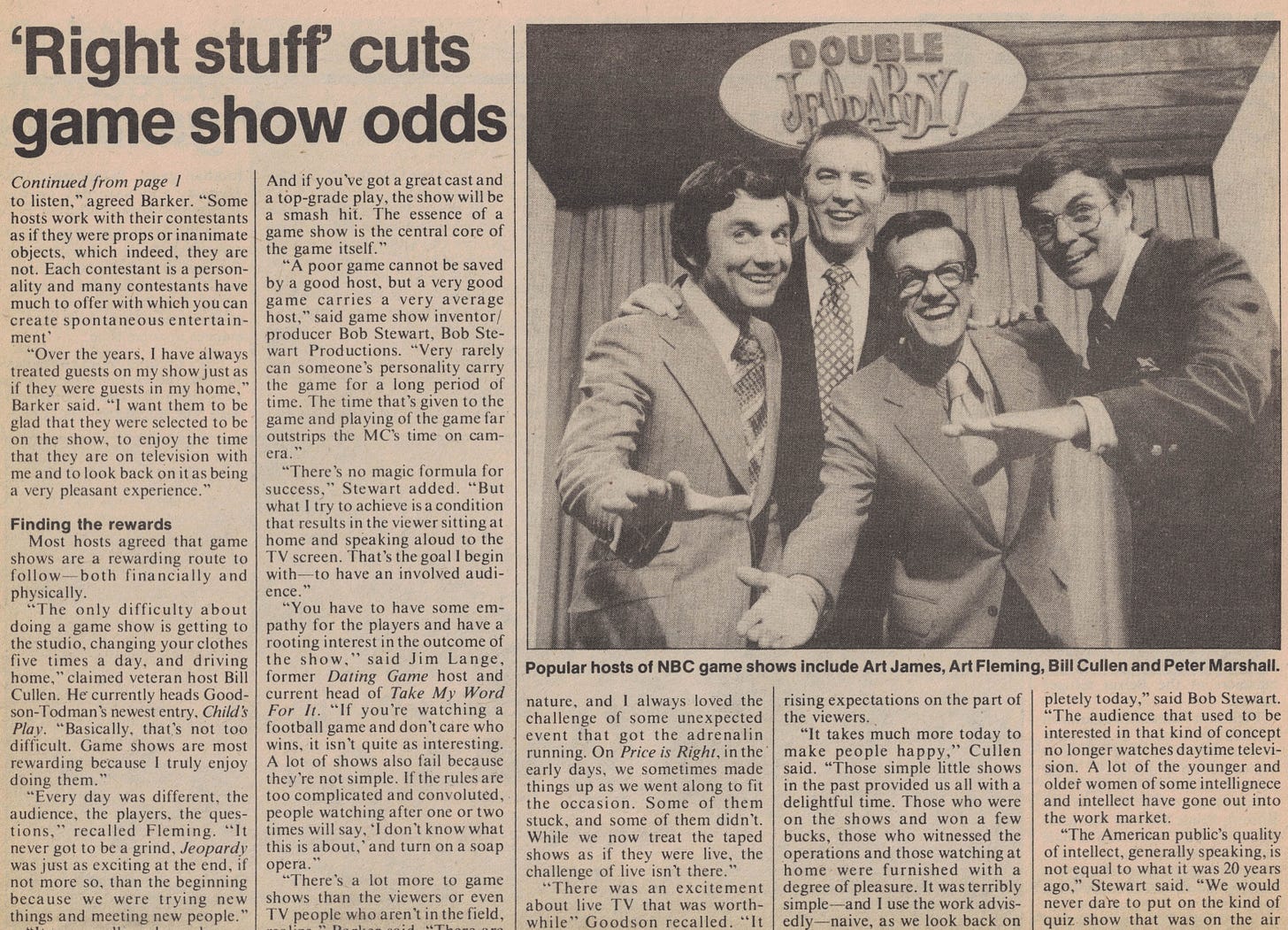

More than 1,000 game shows have made their way through American radio and television, which speaks well of us as a playful and inquisitive species. But there’s a much smaller priesthood of hosts who bounced among the successful ones, men who possessed whatever mixture of affability and talent necessary to make repeat appearances in people’s living rooms. In addition to Cullen, it included people like Bob Barker, Allen Ludden, Art Fleming, Peter Marshall, Gene Rayburn, Bob Eubanks, Art James, Wink Martindale and Jim Lange.

While women have served as panelists or assistants, there have been next to no female hosts. Unsurprisingly, Betty White was one of the few, even if it was on a show called Just Men.

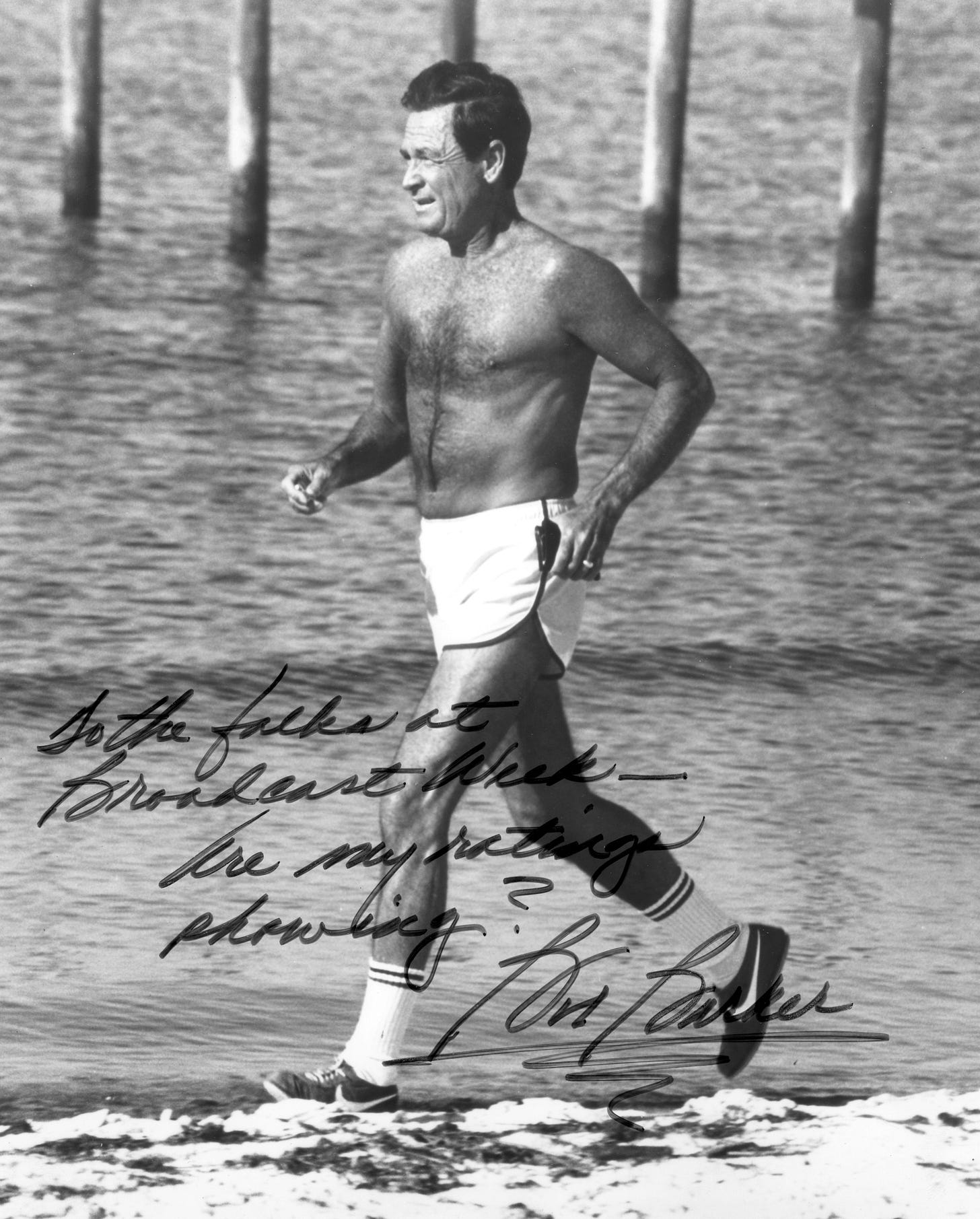

I got to talk to some of my favorites for a round-up on game shows for my newspaper, Broadcast Week, in 1982. Among them was Bob Barker, part Sioux Indian, longtime animal rights activist, vegetarian and host of two game shows—Truth or Consequences and The Price is Right—across almost six decades. He answered his home phone to a cacophony of dogs, reminding me of his standard TV sign-off to “have your pets spayed or neutered.”

Barker is currently 98 years old, but at the time was happy to share a beefcake photo of himself running along the beach (“Are my ratings showing?). In my interviews, he came off as the Meryl Streep of the game show community, a doyen capable of speaking on behalf of the industry and his colleagues.

“To do this type of show, I don’t care how much natural talent you have, there’s no substitute for experience,” he told me. “Because training-ground radio stations have stopped doing live shows from drug stores and supermarkets, on-air personalities have had little chance to learn how to deal with non-professionals in an audience.”

The most important skill is the ability to listen, he went on.

“Some hosts work with their contestants as if they were props or inanimate objects, which indeed, they are not. Each contestant is a personality and many contestants have much to offer with which you can create spontaneous entertainment.”

Others recalled the migration of game shows from New York City to larger quarters in Los Angeles in the 1970s. There was a consensus that contestants were sharper back East, with Art Fleming, a TV and movie actor and original Jeopardy! host from 1964-1979, the most outspoken.

“In L.A., they talk about three things,” he griped. “’Did you buy your clothes at Gucci?’ ‘I’ve got a new tennis instructor,’ and, ‘You wouldn’t believe my new diet.’ Cover those three things, and you’ve had it. So we had a major problem in getting contestants with some semblance of the smarts.”

The West coast was better suited for what producer Chuck Barris called “people shows,” like The Dating Game. “There were no correct answers,” said host Jim Lange, a longtime radio announcer. “People weren’t required to have a great deal of knowledge, just come up with an answer, and they were judging themselves.”

Inevitably, the pace quickened as the years went on. When The Price is Right was revived in 1972, its production company, Goodson-Todman, realized that it would need an overhaul that kept it colorful and in constant motion, and that’s when they hired Barker.

“Physically, that show was not for me,” Cullen admitted, having survived a bout of childhood polio. “Barker was agile and tall, so he had the chance to defend himself from all of that spontaneous exuberance.”

He might have been talking about a thousand contestants, but one in particular made every blooper reel. She lost her cap— and her tube top—after jumping up and running down the aisle to play the game.

“These people have taken leave of their senses,” Barker deadpanned on camera. “I have never had a welcome like this.”

Fleming would have agreed. “Today you’ve got to jump up and down and have a seizure on camera to show that you’re having fun,” he said. “Shows now are ridiculous, and they’re not entertaining at all.”

Yes, that horse left the barn pretty quickly. And it was wearing a tube top.

I got my parents tickets to the Barker-era Price is Right when they visited me in Los Angeles in 1992. It taped during the day at CBS Television City at the Fairfax Farmer’s Market, storied home to The Carol Burnett Show, All in the Family, Three’s Company and other sitcoms and variety shows of the 70s.

Audience members were lined up in cattle chutes, given numbers and did short interviews with staff who picked out likely contestants to be invited to “come on down!” Fleming would be pleased to know that my folks, although they could be wacky, weren’t wacky enough to get chosen. So they enjoyed the show from their seats.

Mom, next to the pole, and Dad are herded into The Price is Right.

One thing’s for sure, game shows were fun for audiences but they were serious business for producers.

“The game plays the biggest role,” Goodson-Todman’s Mark Goodson told me. “It’s like a Broadway show. If you have a great cast and an insignificant script, the show folds. If you have an unknown cast and a top-grade play, the show will tend to run. And if you’ve got a great cast and a top-grade play, the show will be a smash hit. The essence of a game show is the central core of the game itself.”

Still, it’s the hosts and the announcers I remember.

I wrote copy for Don Pardo— original announcer for The Price is Right, Jeopardy! and later, Saturday Night Live— while working for a little while at NBC. At the time, he had been an announcer for more than 40 years. But he rehearsed. I’d see him sitting in a little announcer booth going over the most mundane lines about what was coming up on NBC later than afternoon.

He told me about his first stint as an announcer on a live game show in the 1950s. The sponsor was Mallowmars, a cookie, and even though he had rehearsed and re-rehearsed his lines, when the light came on he said, in that big booming voice of his, “brought to you by MARSHMALLOWS!”

I think about him whenever I’m doing public speaking, reminding myself how important it is to prepare, but remembering that no matter how much I practice I can still come out of the gate in full screw-up mode. It keeps me humble. And it makes me want some Mallomars.

© 2022 David Potorti

Memory flashback Cuz!