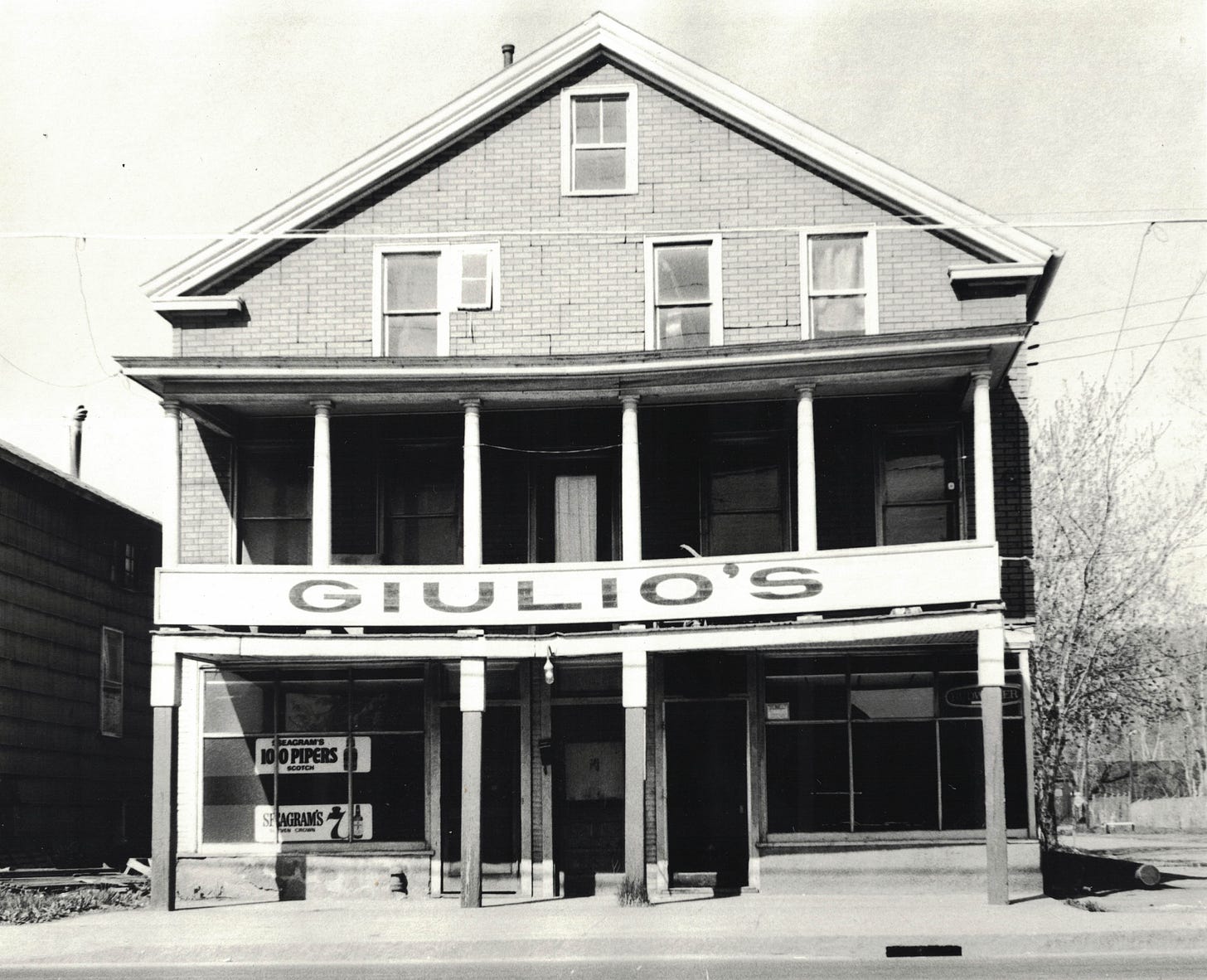

Purity Ice Cream opened in 1936, a rare mom and pop shop that outlived its founder and remains in business 86 years later. Most of that time was spent in the same location, three blocks from our house in Ithaca, N.Y., then a working-class Italian neighborhood with competing pizzerias as well as the Ithaca Bakery, which opened 20 years earlier (and also is still in business) and Joe’s Restaurant, site of my parents’ wedding reception, which opened in 1932 (and isn’t). In between was the horizontally-challenged Giulio’s Bar, where a deer once jumped through a plate glass window before leaping back into the street and getting hit by whatever car my friend from high school was driving.

© 2022 David Potorti

As little kids, we’d get loaded into our parents’ car to drive over to Purity’s because it was easier than herding us on foot. If it wasn’t too crowded, we’d park in the same spot by the screen door up front, the neon buzzing as we’d tumble out of the car to stand before the Formica counter. There were racks to the left with big cans of Charles Chips; potato chip bags would not become ubiquitous for a few more years.

We all had our favorite ice cream—mine was Bittersweet, Dad’s was Black Walnut (more robust in flavor than the domesticated English Walnut) and Mom leaned toward Cherry. We’d puzzle over the difference between Vanilla and French Vanilla (the latter was made with eggs), and on special occasions would splurge on a banana split or a sundae. You had two options for receiving your ice cream: paper cups or the familiar wafer cone; sugar cones came later and were more expensive. Dad paid while we climbed back into the car, and held his cone in one hand while turning the key with the other to drive us home.

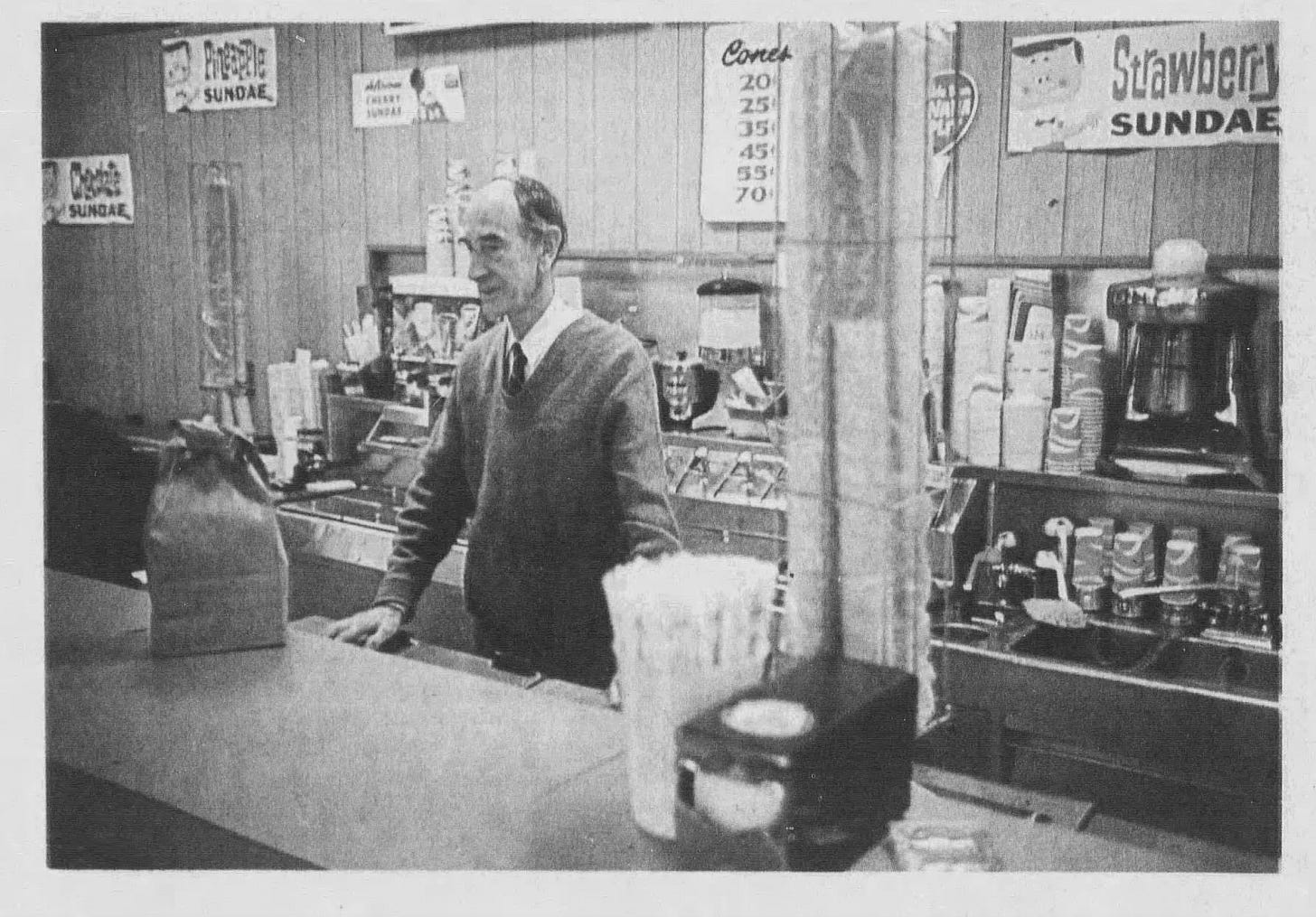

Leo Guentert in 1975 (Photo by Jon Reis)

Purity Ice Cream was founded by Leo Guentert, who graduated from Cornell University in 1920 and worked as a chemist at Nestle before getting into the ice cream business. Evoking the old Pepperidge Farm man from the TV commercials, he was a staid German who never seemed to get older (we joked that he slept in the freezer), but now and then would head off to some sort of getaway in Aruba or another part of the world. He was a kind, church-going pillar of the community, a longtime member of the Elks Lodge and Kiwanis Club, and was a fixture at Purity’s, sometimes serving behind the counter until a couple of years before his death at age 96.

He hired a lot of high school kids, including me.

A Purity ice cream scoop

Leo sat in a glass-enclosed office with a time card punch typical for a small factory, which is where I filled out my paperwork. I never manned the counter, which in the summer months was grueling; there was no line to speak of, and entire softball teams just off the field would be milling about with their orders for milkshakes and banana splits. Instead, I worked in the back, where they manufactured the ice cream on the premises and loaded freezers with their different products. Minimum wage was cheap even then, about $1.60/hour, and the unspoken understanding was that you’d make up the difference in ice cream. It seemed like everyone had their own hidey-hole, a nook where you’d slide a half-eaten ice cream sandwich you could nibble on as the day went by.

I was enlisted to make some sort of delivery, and was introduced to an unmarked and well-used bread truck. It had no door, no seat belts and no gas pedal, just the vertical stub where the pedal used to be, adding an interesting ergonomic twist to accelerating while trying hard to not fall out of the cab.

I’d unload milkshake mix, heavy cream in vanilla or chocolate flavors in metal farm cans that I’d pour into smaller containers for use behind the counter. Discretely dipping a paper cup into the mix, I’d savor the creamy mixture like a wine connoisseur and get a jolt of sugar that would keep me going for the rest of the day.

Dry ice was sold for those wanting to preserve the ice cream over a distance; it also was perfect for Halloween punch bowls or science experiments because it bubbled and released fog-like vapor when dropped in water. These 50-pound blocks of solid carbon dioxide were stacked in a kind of metal dumpster that I had to climb into to reach. Because the CO2 was always melting and releasing gas that was heavier than air, the challenge was to descend into the fumes and grab what you needed before passing out. For this task I was given a collection of canvas gloves, identical in one respect: every fingertip had a hole worn through it, which meant that your skin stuck when it touched the 109 degree-below-zero blocks. Lacking the ice tongs that probably went missing in 1942, I would hoist a cube onto a band saw, the ice squealing as I sliced it into more manageable pieces.

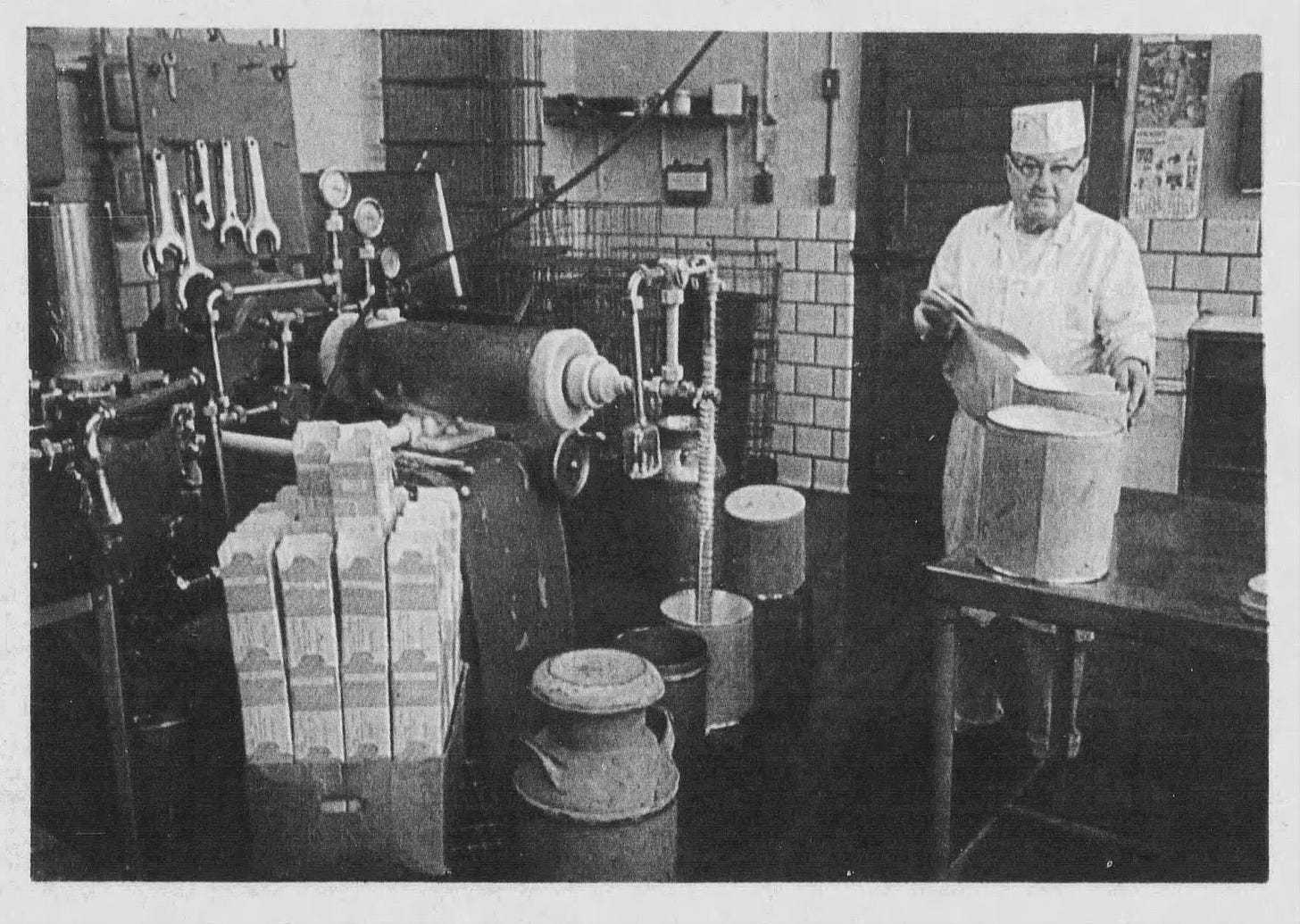

Photo by Jon Reis

At the time, they were still manufacturing ice cream on the premises, and I got to witness the creation of my favorite Bittersweet one day. There was a large, round tub of cold Vanilla ice cream with a beater turning through; from the side, a steady stream of hot, melted semi-sweet chocolate issued from a tube, freezing into flecks as it drizzled in, giving it an egg drop soup texture that remains the Bittersweet trademark. Fudgsicles were poured into molds and frozen with wooden sticks poking out of the ends, and ice cream sandwiches were assembled like, well, sandwiches, and slid into glassine wrappers.

There was an enormous freezer where I lugged and shelved countless half-gallon and gallon tubs of ice cream, mostly for delivery. The freezer was why I didn’t last long at Purity’s—as refreshing as a visit to an ice-cold chamber might be on a sweltering day in July, going back and forth from the heat to the cold started to do a number on me. That, and unloading 10,000 sugar cones from a truck one afternoon.

Purity’s stood its ground through my childhood, young adulthood and adulthood, a place relished by visitors and, I think, never quite appreciated enough when I lived three blocks away. Not just for the ice cream, but simply for staying put, staying a place where my grandparents, parents, aunts, uncles, cousins and my own children breathed the same air, sat at the same outdoor picnic tables, and heard the same neon buzzing. How many places do you know like that?

Sure, they made changes in recent decades— adding soy and gluten-free ice cream, sandwiches, brownies and bike racks—and at one point sold t-shirts bearing a pretty good caricature of their founder.

And they still sell dry ice.

© 2022 David Potorti

This is such a great capture! My dad told stories of when he worked there. I can't remember them fully but of course lots of mischief was involved. Thanks for writing this.

A marvelous memoir of a magical ice cream store. Well done, Dave! And you're right, their Bittersweet is the absolute best.