Two record albums monopolized the drug store cutout bin when I was a kid.

The first was Lord Sutch and Heavy Friends, a 1970 release featuring “Screaming” Lord Sutch, Led Zeppelin's Jimmy Page and John Bonham, guitarist Jeff Beck, and other superstars of the day. The cover showed the dandy leaning on a Rolls Royce painted with a Union Jack, and the record was promptly disowned by the players—who thought it was just a jam session—when they learned of its release.

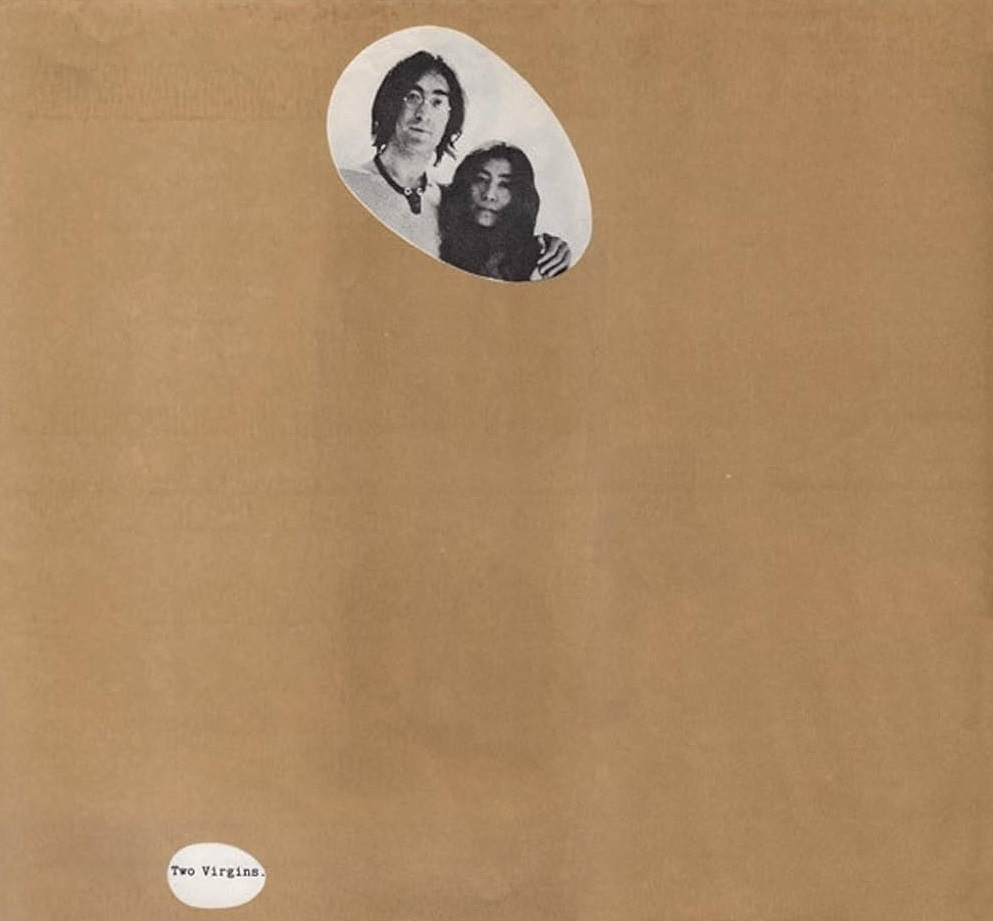

The second was John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s Two Virgins, a dreadful sonic dispatch from Ono’s epiglottis, featuring Lennon’s whistling and what sounded like the mating calls of the humpback whale. It was wrapped in brown paper because of the full-frontal nude photo of the couple on the cover. Exactly two people thought this was a good idea.

Even at 99 cents, I didn’t buy it.

The Zenith 6R886. Credit: Bill Potorti

It wasn’t ever thus. Growing up, the music in our home came from my parents’ Zenith tube radio/ phonograph, circa 1947, which sat atop a handsome varnished cabinet with shelves below that held 78 rpm shellac records from Perry Como, Al Dexter and His Troopers or the Sons of the Pioneers. It even sported an innovation: a tall post with a moving tab held multiple records, piled on top of each other, and when the first one ended, the tone arm—the Cobra, check out the eyes— would swing back, prompting the next disc to drop into place. Convenient for the listener; not so hot for the records.

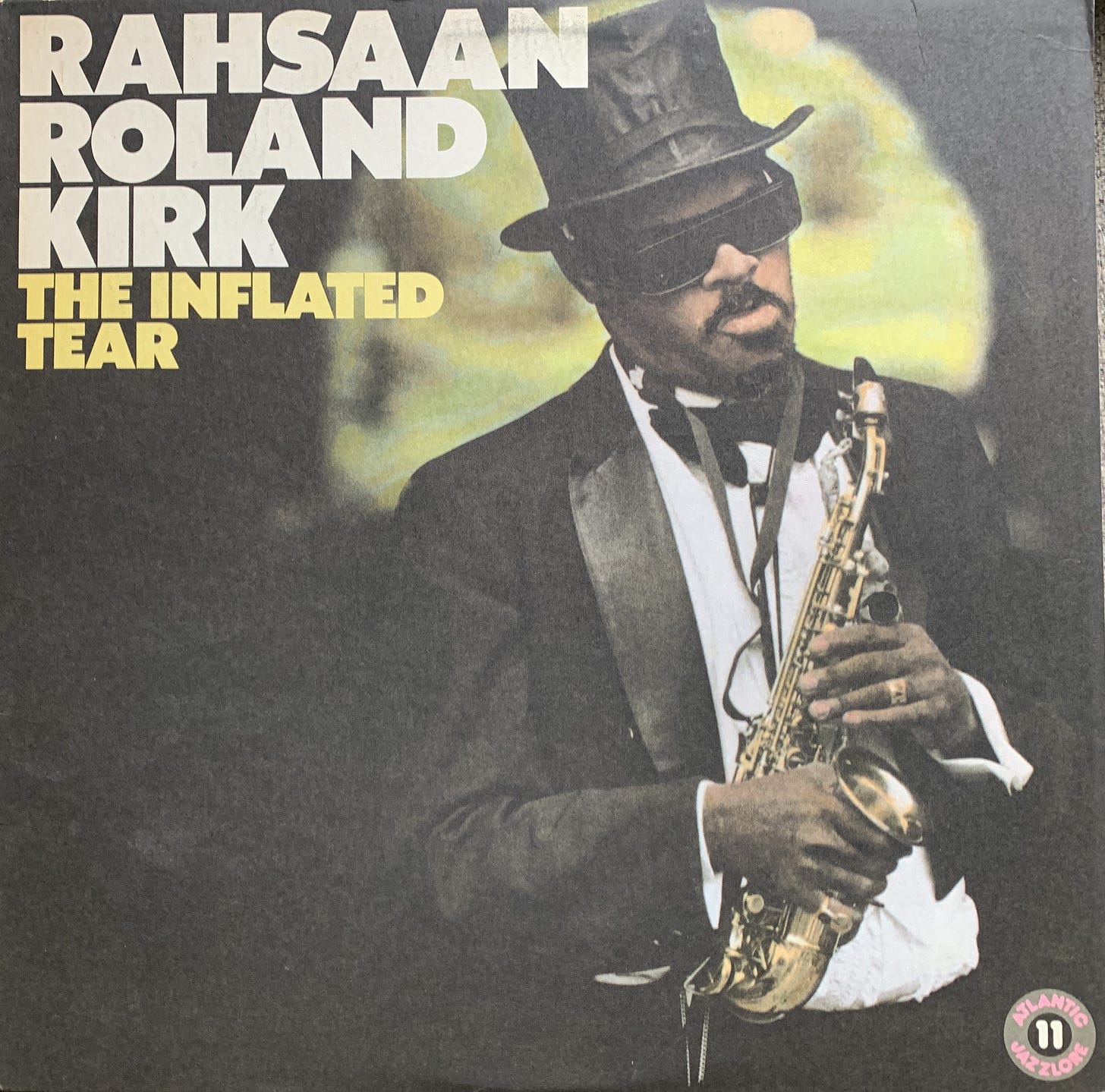

Later on, mass-market albums were democratic, kind of like newspapers for young people. The cardboard covers were artful, something you’d handle while listening, dwelling on the large images and photos and maybe even reading the lyrics written across the inside. Everyone had a few, and everyone had a record player. Sure, there were jazz aficionados with their pipes and their Marantz reel-to-reel tape contraptions, but even kids could have a little all-in-one suitcase player for their single-song 45’s.

When I was 14, my winning drawing in an art competition earned me a full-blown taupe plastic luggage-cum-record player that folded open, with outboard fabric-covered speakers. I was a romantic in those days, opting for albums of Jimmy Webb tunes sung by Richard Harris, or garage virtuosos like Emmitt Rhodes. Multiple plays would produce snaps, crackles and pops, and the occasional skip might be remedied by taping a nickel on top of the phono cartridge. Note: do not tape a nickel on top of the phono cartridge.

The full-size album covers not only had acres of space for art but also for mischief. Artist Andy Warhol conceived the cover for the Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers, featuring a denim-clad torso that came with an actual zipper. Record stores complained that the bulky slide was damaging the discs during shipping, so a remedy was devised: the zippers, one at a time, by hand, would be unzipped halfway, so the metal tab would line up with the center hole of the adjacent record.

A few years later, Some Girls’ elaborate die-cut cover included images of Farrah Fawcett, Judy Garland, Raquel Welch, Marilyn Monroe and Lucille Ball, instantly drawing lawsuits from the stars or their estates for using their likenesses without permission. I remember a college friend sprinting to the record store to buy up copies before they got pulled from the shelves and rehabilitated.

Neil Innes and Eric Idle’s brilliant Beatles’ parody group, the Rutles (“The Prefab Four”) released a vinyl soundtrack album from their 1978 TV show, All You Need is Cash. They aped four Beatles albums at once: Meet the Rutles; Tragical History Tour, (featuring, “Your Mother Should Go,” and “All You Need is Lunch”); Sgt. Rutters Darts Club Band and Let it Rot. A simulacrum to make your teeth hurt, it was arch all the way down to the record sleeve, which promoted mock albums by other artists including Crosby, Stills, Nash, Young, Gifted and Black.

Rhino Records, which occupied a Los Angeles storefront just south of UCLA, held weekend parking lot sales of used discs when I lived in the area in the 1990s. Long tables held rows of cardboard boxes with records in the thousands for 25 cents each. It was a fun browse, and a philosophical one: you could trace the career of an artist from hopeful beginning to last stand—those who didn’t go for a quarter got melted back into vinyl.

Akin to independent bookstores, independent record stores like Rhino were places to hang out and enjoy visiting artists. Sporting a colorful agbada, Nigerian drummer Babatunde Olatunji, on site for the release of Healing Rhythms, Songs and Chants, led six of us outside to demonstrate a spit take of whiskey—something about warding off evil spirits—followed by the ritual pouring of a libation to the ancestors, in this case onto the sidewalk, as puzzled drivers passed by.

Still, indy record stores fell like dominoes as new technologies and large chains took over, with the physical Rhino store closing its doors at the beginning of 2006. But today, vinyl is selling again: US record sales went up 22% in the first half of 2023. Modern turntables might even have USB ports allowing you to dub the recordings in analog fashion onto your PC. And if you want a real challenge—or you’re completely nuts— you can “pirate a record the hard way” with a silicone rubber mold and liquid plastic. Whatever disc I’d cobble out of this process would resemble a scrambled egg that needed more than a nickel to hold the tone arm down.

I interviewed a man who collected and lovingly restored 78 rpm singles, an early 20th century standard, into CD compilations. He told of the old days when you could still find rare specimens in shellac at the Sunday morning flea market, where he’d arrive early, until another collector started arriving earlier. So he’d arrive earlier still. And on it went.

He invited me to his house for a listen, a sanctum sanctorum where two comfy chairs faced a record player sitting under a small shelf with singles in identical paper sleeves. As I sat, he selected a record, brushed it off, cued it up, and sat down in the other chair. We listened for about two and a half minutes. He rose, lifted the record, slid it back into its sleeve, and returned it to the shelf. Then he took down another one. If it wasn’t a species of religious experience, it was certainly a Zen one that required mindfulness and attention.

I’m coming to appreciate that practice as I delve into my old record collection again—the tender holding of the disc, the cleaning, the careful hover of the tone arm, the attention paid to the needle’s descent onto the disc, and the shucking sound it makes in that final groove as a reminder that you need to lift up the tone arm again (direct drive turntables, like manual transmissions, require you to do everything). It’s a serious form of meditation.

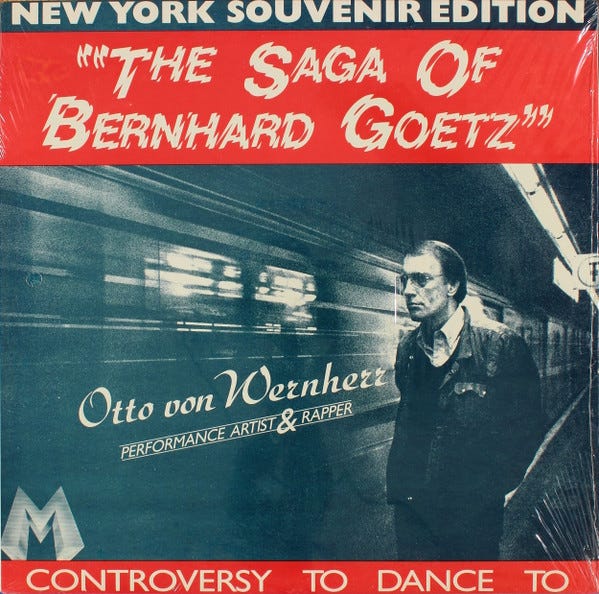

The experience is even deeper when it’s an album that isn’t streaming. Usually there’s some dispute, legal or personal, with artists or labels, or an album’s orphaned status, that keeps it out of the ether. There’s Louis Meyer’s Wailin’ the Blues, that I bought at the little bar where he was playing; The Saga of Bernard Goetz, the so-called subway vigilante, that I bought from a guy on the New York subway; and Scoop’s Last News Show, a promo radio disc featuring The Swami From Miami, who makes charts for the Jewish ladies.

At a time of Brave New World-style over-organization, there’s something calming about playing some oddball vinyl in my home and knowing that no one else on earth is listening to exactly the same thing at exactly the same time. No bot is taking notice of what I’m playing, or when, or how many times.

Just my dog, and she’s not talking.

Love the descriptions of the albums, the artwork, and the sound of the needle when the side of ended. I’m remembering a Hawaiian themed party we had in my studio apartment with everyone in flowered shirts and leis, travel posters on the wall, and an album we played of luau music.