Brother Bill Potorti with Louise Hamster

Woolworth’s in the 1960s had it all: flannel shirts, record albums, salt for sidewalk de-icing, a tube tester for your TV, and rolls of Tri-X film. I spent a lot of time in the stationery aisle, somehow drawn to the aroma of ink and paper from some past life. But the pet department was where the action was, with its carnival-like rows of fluorescent glass cases, each containing an exotic and exciting specimen of life. Here you’d find horned toads, baby turtles, parakeets, and that workhorse of small mammals, hamsters.

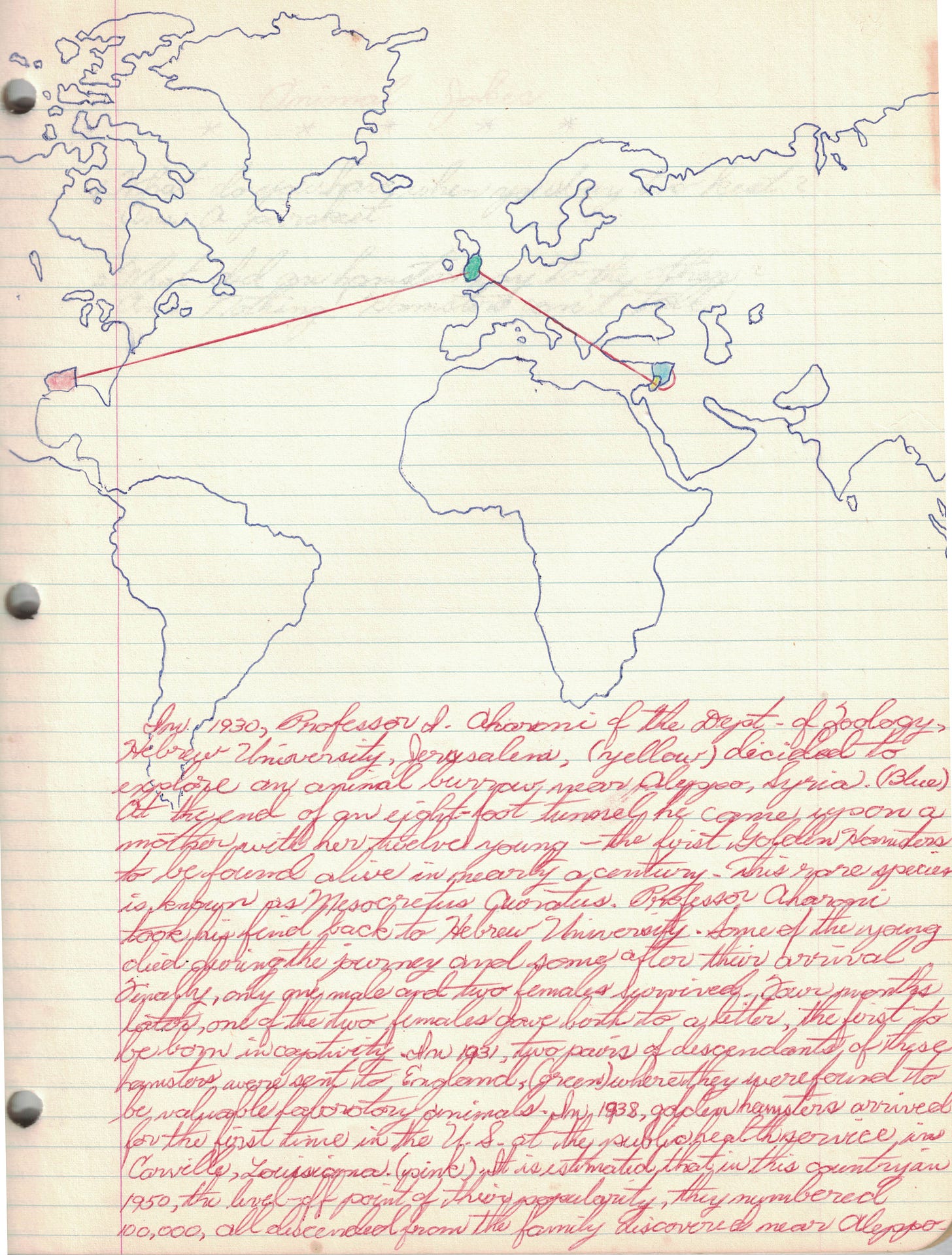

I took hamsters very seriously, researching them with all the rigor of a budding anthropologist or young OCD sufferer. In my Pet Logbook Vol. II, under the tab marked “Animal History,” I wrote:

“In 1930, Professor I. Aharoni of the Dept. of Zoology, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, decided to explore an animal burrow near Aleppo, Syria. At the end of an eight-foot tunnel he came upon a mother with her twelve young—the first Golden Hamsters to be found alive in nearly a century…”

It was a compelling story, from wherever I got it. Most of the young died in transit back to the University, but one male and two females survived and pretty much got the ball rolling—first to England, where they were used in laboratory research, and then to America, where they also became pets. Their numbers grew exponentially and many wound up in Woolworth’s and other five-and-dime stores across the land, golden, cream, brown, and piebald, palm-sized and docile with their little feet and stubby tails.

There was all the required equipment, the steel cages with narrow bars, the cedar shavings somehow colored green, the metal exercise wheel, the little baby bottles with the curved steel spouts for water, and some kind of tray to serve up the mixed seeds that made up the animal’s diet. Hamsters had pouches in their cheeks that they’d stuff to bursting with seeds before unloading them in nests that, in this case, were about eight inches away. But such was instinct.

Pinterest (Adam Godfrey)

My mom was freaked out by hamsters, which she thought had no bones, a perfectly logical conclusion drawn from their knack of surviving the unintentional abuse of getting sat on, dropped or squashed in any number of ways. After church on Sunday mornings, we’d finish breakfast and give whatever hamster we owned at the time free rein to climb over the empty dishes, leaving yellow egg footprints on the tablecloth as we kept an eye out in case it went full lemming over the edge.

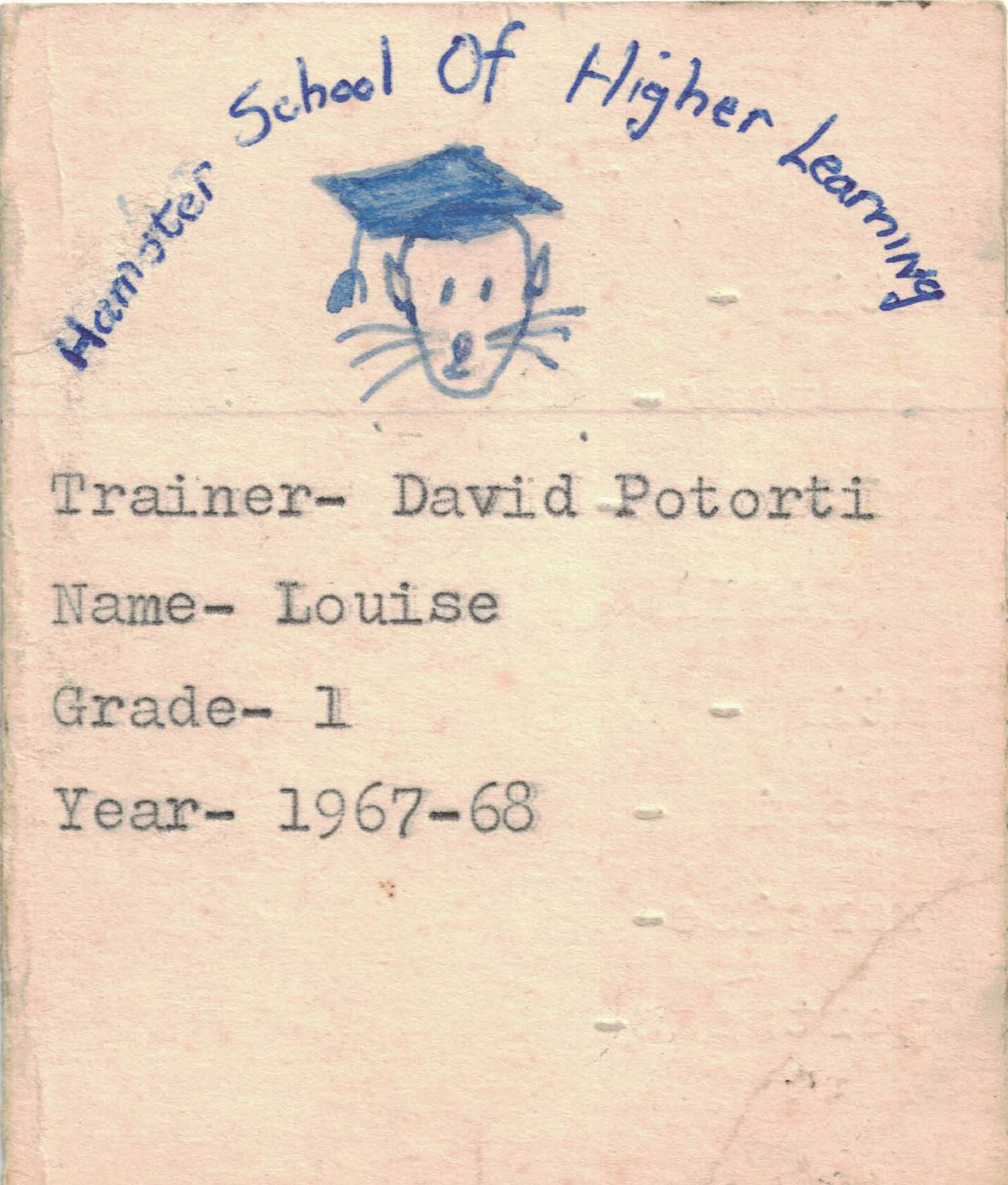

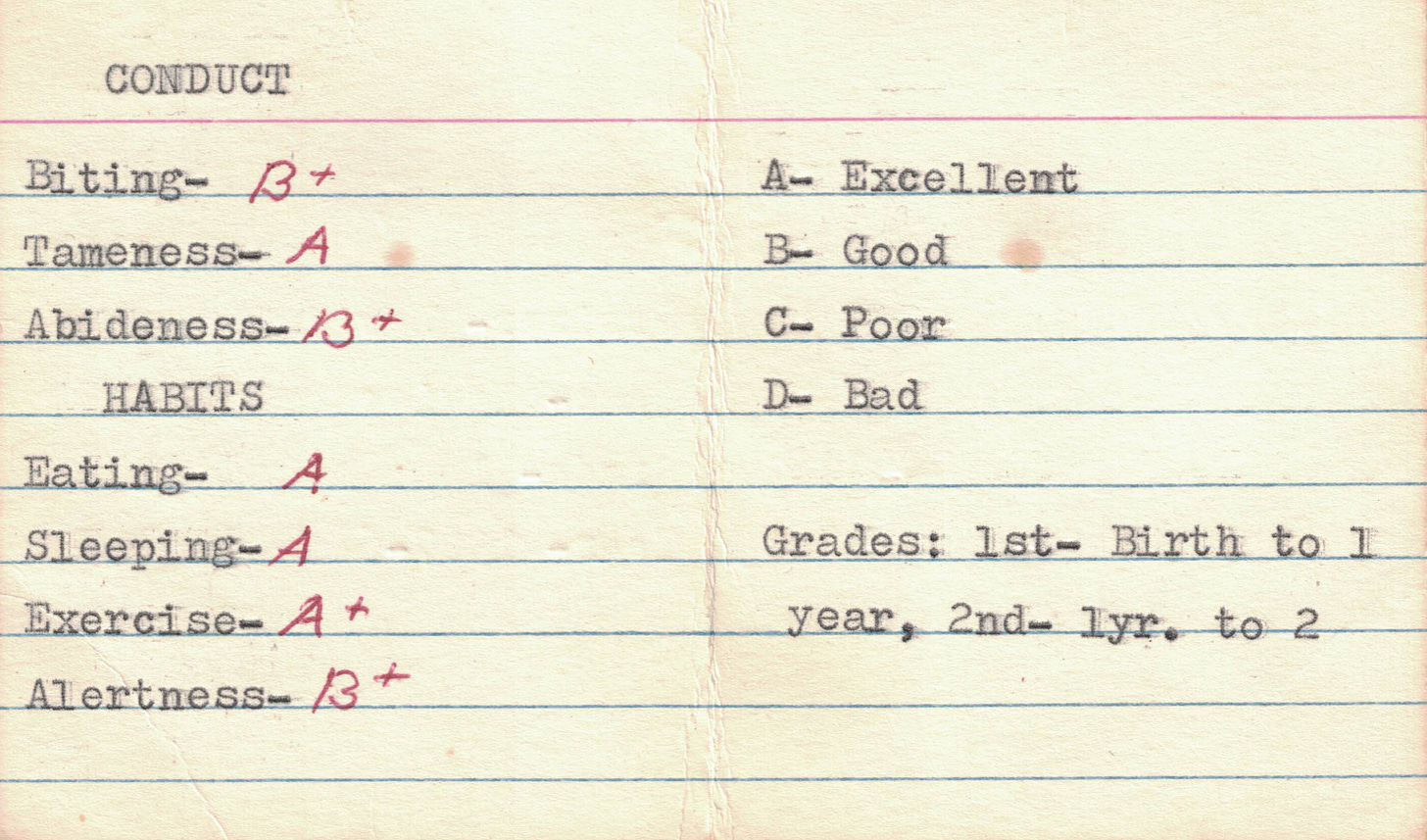

Unlike most hamsters, ours got report cards. The Hamster School of Higher Learning issued its typed assessments in the style of my Catholic elementary school report cards, tracing each animal’s progress on a month-to- month basis. There were A through D ratings on conduct including biting, tameness and abideness, as well as habits including eating, sleeping, exercise and alertness.

An accompanying hand-drawn spreadsheet listed the creatures’ names, cagemates, escape history, whether they had been mated, and their color-coded ailments, which included cold, diarrhea, overgrown teeth, paralysis, overgrown nails, heart attack or other internal injury, viciousness and… cannibalism.

Yes, it was a rite of passage to breed them, somehow figuring out when the female was in heat and introducing a male into her cage to get the deed done. It also seemed to be a rite of passage to watch in horror as the mom ate her newborn babies for no discernible reason—maybe she got spooked by the sound of the television or vacuum cleaner, or was driven to madness by the smell of Formula 409. Hamsters had no problem reproducing, just not around our house.

The other behaviors were easier to explain. Who isn’t a little testy when they’re constipated? Who doesn’t get a little nippy when they’ve got a cold? And who doesn’t get paralyzed after getting sat on by a 60-pound kid? Even these patient creatures could get pushed too far. And eventually, they’d die, if they didn’t escape first and disappear down some furnace grate, never to be seen again.

Louise, vacationing in the Hamster Home

We had a country uncle, one with hunting dogs and shotguns, a bagger of ducks and deer, who’d fall asleep on our couch with the game on after Thanksgiving dinner and a couple of beers. He had an early satellite dish, easily six feet across, on his verdant property, which pulled in distant NASCAR races and Malaysian bass fishing tournaments. And he brought his keen sportsman’s point of view to bear during a visit, when he met one of our elderly hamsters, sickly and clearly in decline.

“Why don’t you just wrap it in a towel and hit it with a hammer?” he suggested matter-of-factly.

Stunned, I would have nothing to do with such barbarism. No, this hamster would die of natural causes and get buried in a frozen orange juice container as God intended.

And so it did. Three G.I. Joes, the original 12-inch ones, assisted with the funeral and saluted over the burial site in our yard. The headstone was a smooth, flat rock with a magic marker epitaph:

Here lies Herman Hamster

He died quite unexpected

He lived a clean and happy life

But by dying then he wrecked it

Taps was played on a Honer melodica, and Herman joined the procession of his departed fellows— gerbils, mice, and yes, the parakeet—some dispatched in the sliding drawer of a wooden match box, every one a beloved member of the family, each honored as it was laid to rest, and none of them wrapped in a towel and hit with a hammer.

© 2022 David Potorti

😂😂😂 This is your best work yet. I’m dying. I was a huge hamster fan. Or so I thought until I read this. Seriously, you need to reach out to the New York Times and see if they will publish this. If you don’t, I will. It’s absolutely brilliant.

Good story. Great storytelling.