Drawing the Line

Sometimes art is its own reward

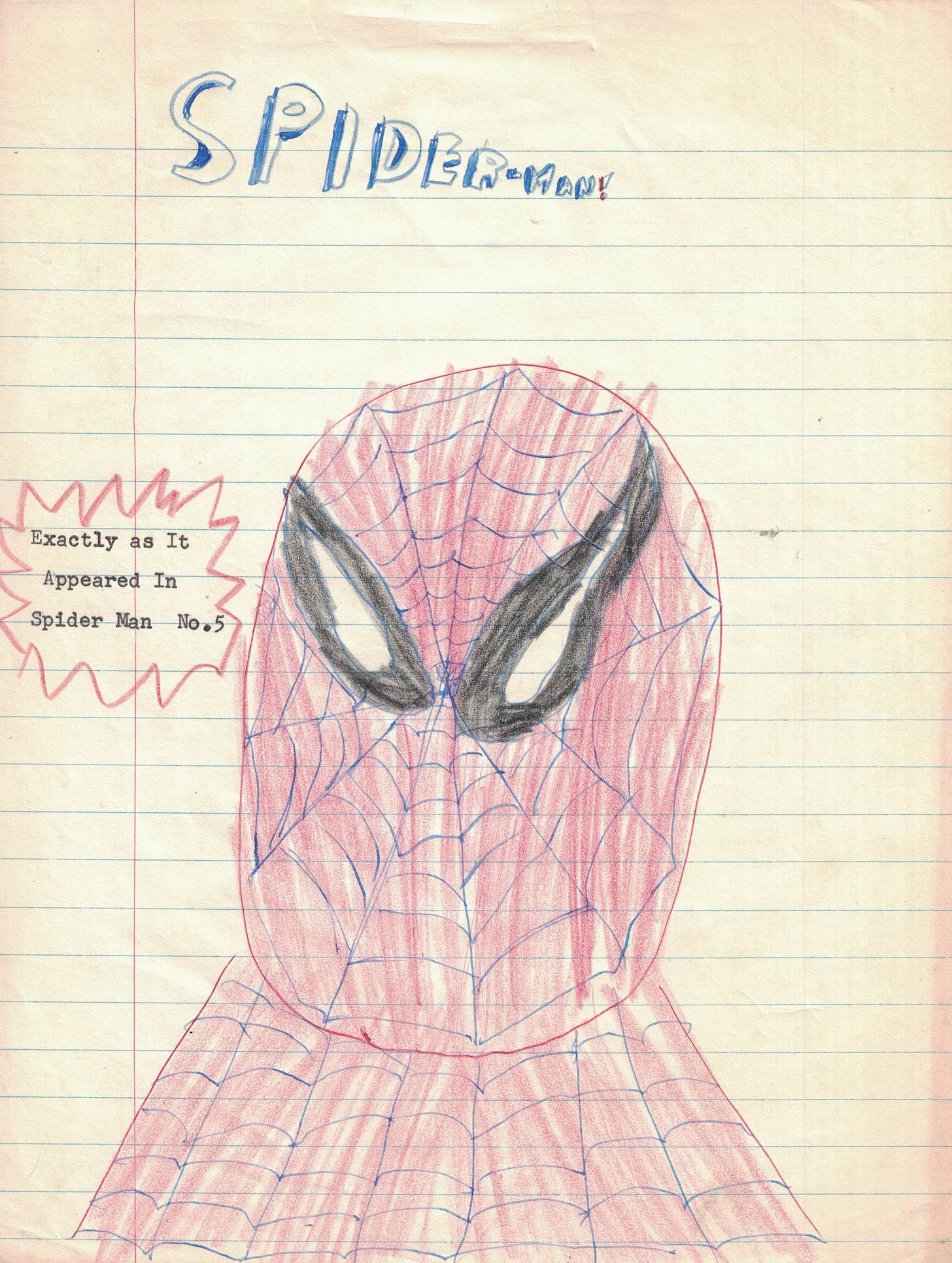

Long before there was a Marvel Cinematic Universe, there was a cartoon universe in my head. My imagination was ignited by the great artwork and storylines of guys like Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko and John Romita, working on paper in that golden age of comic books in the 1960s.

The prospect of a new edition of The Incredible Hulk, The Amazing Spider Man or a DC Comics entry like Tales of the Unexpected made for a big night out: I’d walk three blocks to Jake’s Red & White, a wooden-floored corner store across the street from my elementary school. In my memory, it is always summer— the swinging screen door, the buzzing lights, the absence of air conditioning. The rotating rack of comic books was in the back, each specimen running 12 cents, and after making my selection I’d pause at a waist-high freezer to pick up a Fudgesicle, a Cheerio bar, or a Creamsicle. I’d blow into the wrapper to free the treat on a stick, striding home just a little faster knowing the twin satisfactions that awaited me.

Those comics couldn’t have been more influential in my young life. My hand-drawn tributes followed, beginning as actual copies of the covers, including the upper left-hand seal from some invented comic book authority, moving into freestyle drawings and lifted storylines.

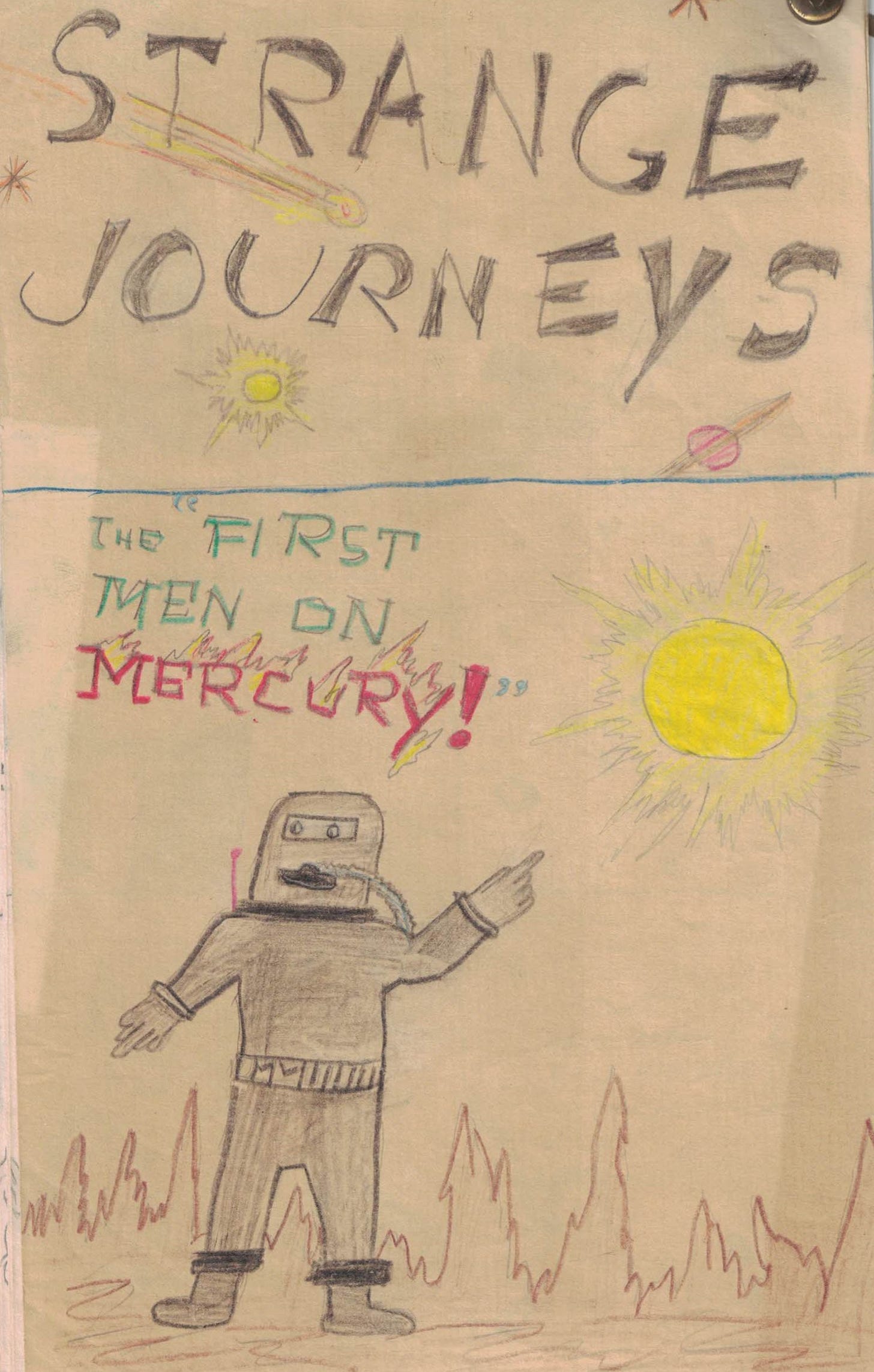

The First Men on Mercury (“We must be sure to land on the cold side!”), Torch vs. The Beetle (“My wings are made of bullet-proof steel!”) and Half Man…Half Reptile: The Lizard (“Begone! This swamp is mine!) were tense reading, even today. A little less compelling were my original strips, like Iron Man vs. The Green Goblin, whose entire storyline tracked the progress of the former’s boot as it squashed into the latter’s head: “The End”.

Then there was Super Kumquat, battling The Cucumber Gang as it sowed havoc in Fruitville. I had never seen a kumquat, although I’d heard Mr. Fitchmueller bellow for 10 pounds of them in the W.C. Fields film, It’s a Gift.

Whatever the subjects, my drawings seemed to follow a genetic directive governing all kids’ drawings: googly eyes, lines for mouths, three-dimensional moves captured in one dimension. I have great regard for contemporary cartoonists like Dav Pilkey (Captain Underpants) and Lynda Barry (Ernie Pook’s Comeek) who have been able to tap into that kid consciousness as adults.

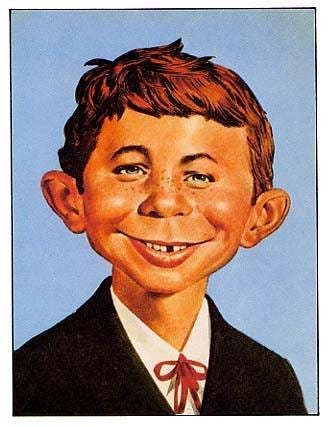

Alfred E. Neuman: What, me worry? Credit: MAD Magazine

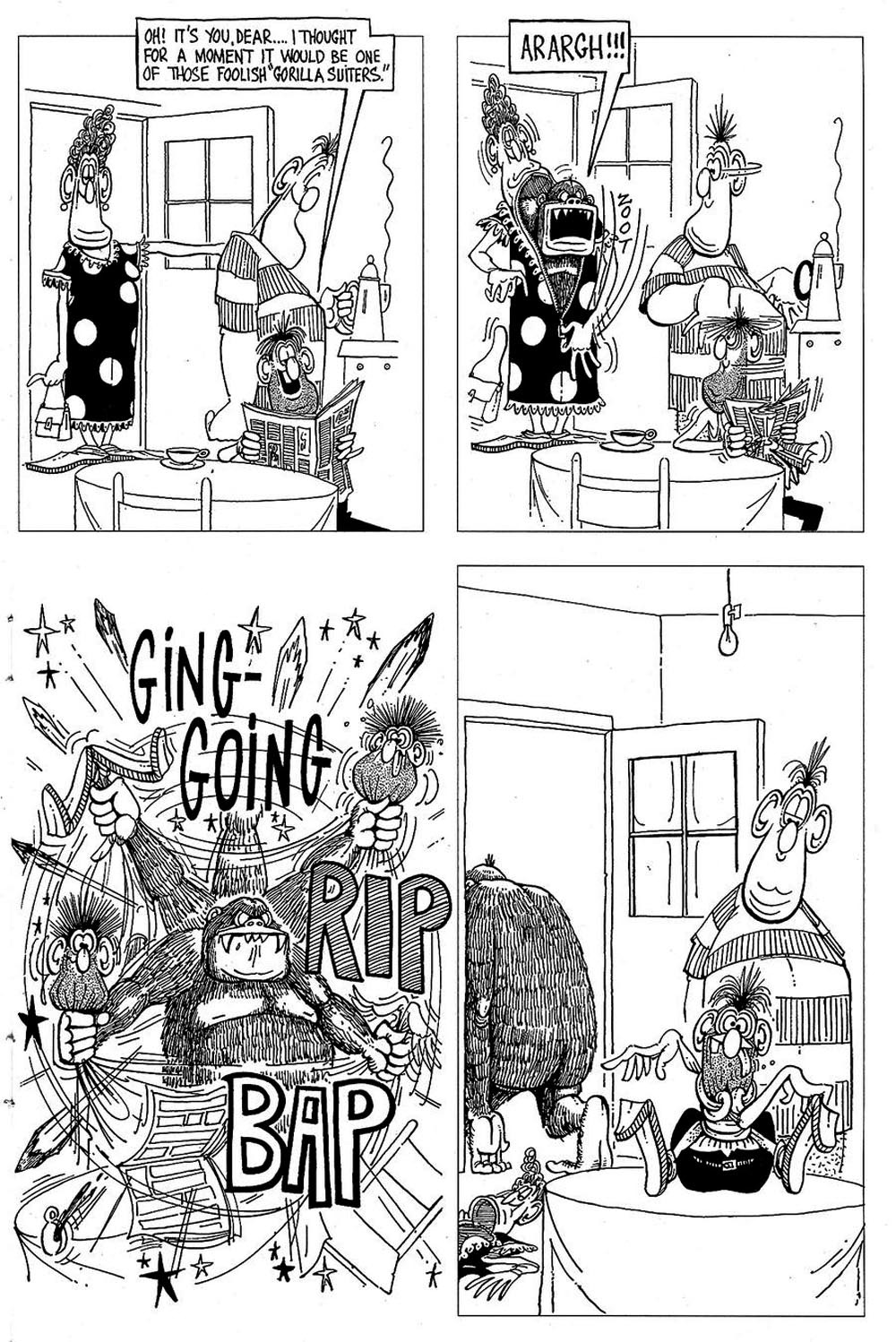

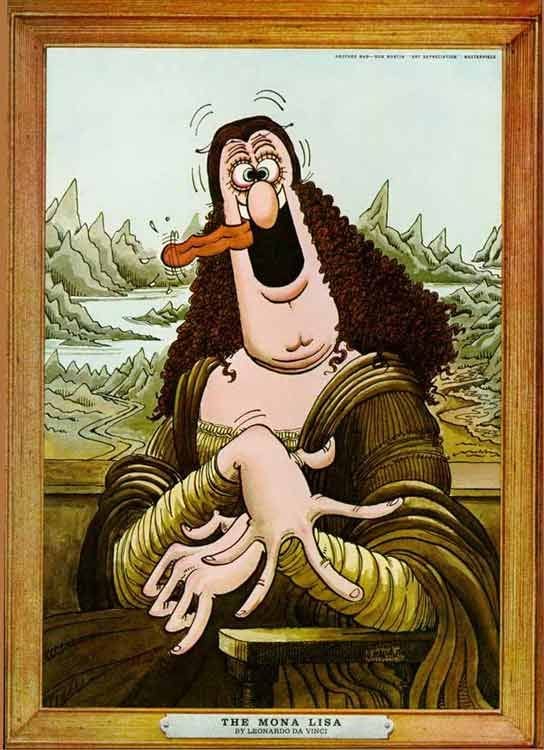

Still, the most influential comics of my life appeared in MAD Magazine. Its most enduring image is that of Alfred E. Neuman, designed by an illustrator for hire named Norman Mingo. But the characters who made the biggest impression on me grew out of the head of Don Martin, an illustrator from Paterson, New Jersey, who worked at the magazine for 30 years. Whether men or women, from Captain Klutz to Fester and Carbunkle, they possessed anvil-shaped jaws, hinged feet, heavy-lidded eyes, banana noses and expressions of perpetual surprise and consternation. His comic strip titles, including, “A Guided Tour Through a Steel Foundry,” “At the Knife-Throwing School” and “The Unfortunate Part of Feeding Pigeons Homemade Popcorn,” were portents of strange things to come.

Credit: MAD Magazine

The accompanying sound effects also were legendary, as catalogued—all 1200 of them— in the Don Martin Dictionary. They include FLIBADIP (“Rapunzel letting loose her hair”), STOONG (“Gargoyle hitting salesman in the head”) and CHAKA CHAKA CHAKA CHAKA (“Baby shaking other baby.”) Martin’s vanity license plate read SHTOINK.

His penultimate work was a book-length strip about National Gorilla Suit Day, when a series of uninvited guests arrive at the door of holiday-denier Fester Bestertester, each unzipping his or her skin to reveal a ferocious gorilla inside whose brutal assaults leave him contorted into a variety of surrealist statuaries.

Credit: MAD Magazine

When the much-abused Fester seeks safety by wheeling in a gorilla-detector machine, it, too, unzips to reveal yet another gorilla primed for yet another beating. Sheer joy was generated by anticipating the next guest, and the sound effects accompanying each clobbering.

With my imagination steeped in this absurdity, it was inevitable that my first underground newspaper would follow. The Gumpwa, named after a Delphic junior high school custodian we believed to be named Paul Gadpaw, was run off on a mimeograph machine, a kind of stencil drum with blue ink and a distinctive odor, coaxed into service while a sympathetic teacher looked the other way. It was only a rehearsal for The Munchy Fred—clearly a take on the episodes of Monty Python that were once a late-night staple on public television—and, eventually, a step up in quality courtesy of an offset press shared on the sly by my shop teacher, Mr. Mills.

Mimeograph masters! Sure, the “non-water soluble blue” ink has lost its aroma after a half-century, but the smell remains in my head.

Just as exciting as the writing was spreading the printed pages across the dining room table on a Sunday night, and collating and stapling them by hand. I was a publisher! Even if I got crap from football player bullies, I lugged the papers around, selling them for a nickel (“two for a dime, three for a quarter,” the slogan went, although even my friends weren’t that dumb.) Eventually, a village of benevolent instructors became partners in crime, from women in the main office who slipped me master sheets, to teachers who peddled the paper to their classes.

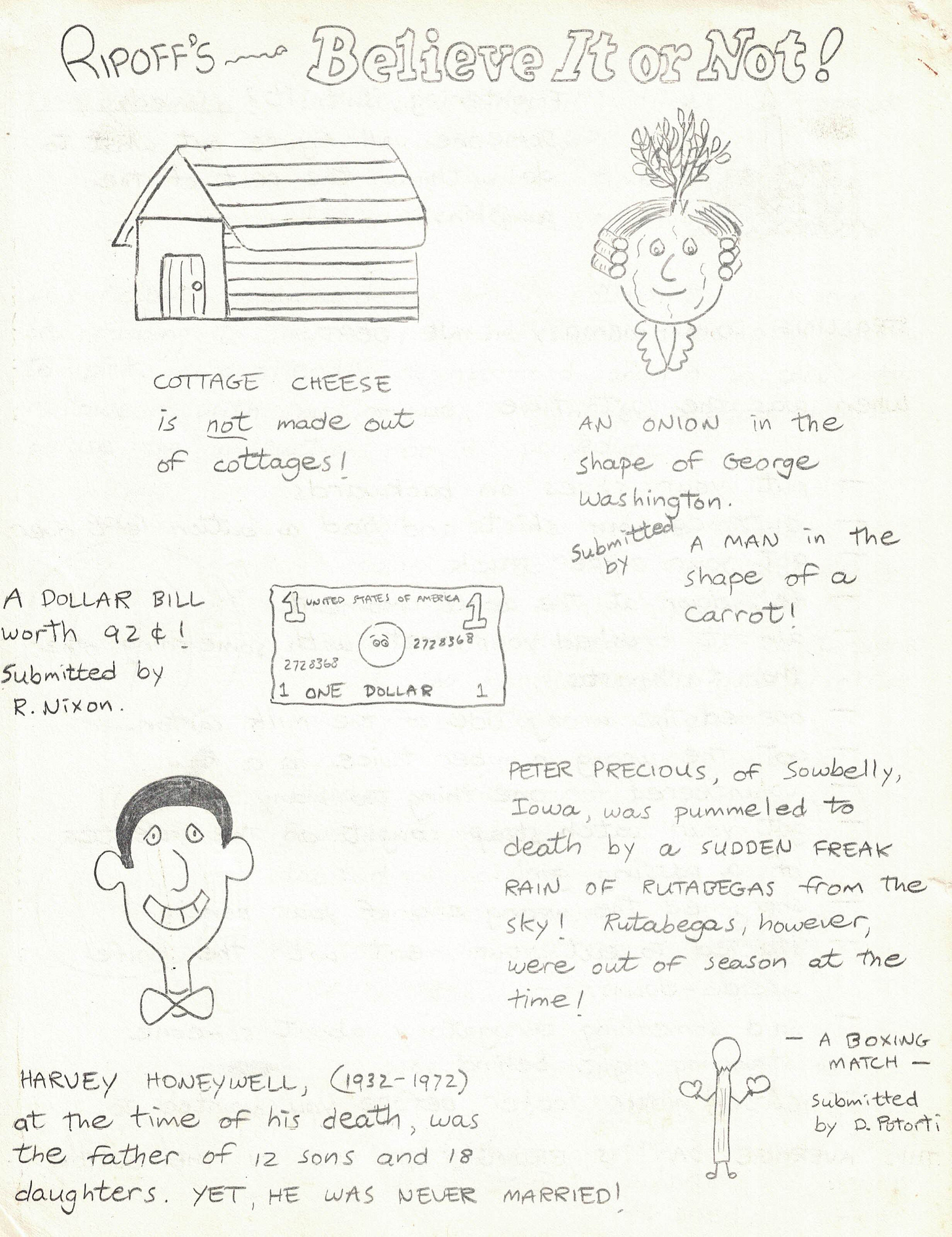

The contents were a stream of consciousness affair based on the mundane goings-on of my life, peppered with joke ads and comic strips worthy of MAD.

There were scientists looking for ways to prevent kittens from growing up; directions for making hollow snowballs; and a survey, signed by students, determining that 100 percent of them had pens. There was a food essay entitled, “The Meatball and Its Need for Hereditary Companionship;” my first review of a school play (“If I tried to dance like that, I’d hurt myself”); and an interview with a school bus that gave no replies to any of my questions. There were fill-in-the-blank letters to Santa, fill-in-the-blank Valentines, and a fill-in-the-blank guide to better conversations.

And there were longer articles, such as an exposé on the notorious Gran Flander’s Food and Drug Empire, whose products included Gran Flander’s Old-Fashioned Lumpy Potato Mix, Stan Flander’s Genuine Honeycomb (“Sweet things come from the mouth of Stan Flanders”), Canned Flander’s Canine Delight Dog Food, Beef Stew à la Flander’s (with the same ingredients), Dan Flander’s Aspirin, Dan Flander’s Fast-Acting Aspirin, and St. Flander’s Children’s Aspirin. In real life, Gran lived and attended church every Sunday at the Creekside House of Salvation in Slime Mold, Nebraska, lived in California on Mondays, lived in Switzerland on Tuesdays, and lived in Argentina on Wednesdays. (“The rest of the week, she lived on welfare.”)

The prospect of making $2.70 on a print run of 54 copies wasn’t something to bank on (even adjusting those nickels for inflation to 37 cents today), but that wasn’t the point; self-expression was. It’s good to remember a time when I took it for granted that people—of course!—would be interested in anything I had to say, even a story about sending away for a “Nutritive Value of Foods” booklet from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and accidentally receiving a copy of “The Skipper’s Course in Boat Safety” instead. I mean, really, isn’t that incredible?

Although social media today give everyone a voice, I’m happy that micro-publishing lives on in small-run “zines” that can be held, felt and experienced with all the senses, and which might endure on paper as evidence of the hand and the imagination of the human who made them.

Credit: MAD Magazine

© 2024 by David Potorti

Fascinating!

Good to see you back in my inbox! Your drawings remind me so much of those comics my son drew. Batman was an important family member from 2005-2008 or so. Wish I had as carefully saved those drawings as your parents did. I remember the mimeograph machine, but not the smell of the ink.