The idea of constructing a homemade arc light probably came from a magazine like Popular Science. It contained everything a young boy could desire: dismantling a chemical battery with your bare hands, unzipping a lamp cord, handling exposed electrical wires, and blinding yourself with an intense light.

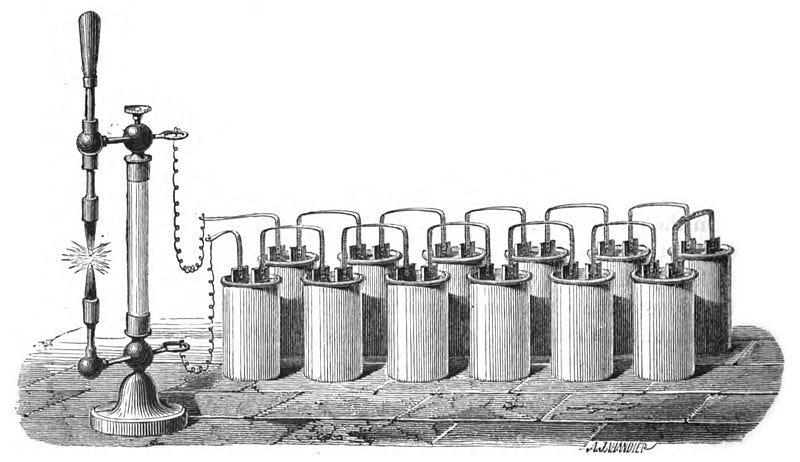

The lights originated early in the 19th century and are attributed to Humphry Davy (a name befitting either a British inventor or a pirate). They went into use in mills, factories, stores, movie sets, and in outdoor spaces like streets and parks.

Augustin Privat Deschanel, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

They also were used in searchlights and movie theater projectors because of their sun-like intensity. In fact, the 22 minute lifespan of the lights, when used in projectors, was the reason that movies originally were shipped on 2,000 foot film reels that each lasted about 22 minutes; as both the light and the film reached their end, the projectionist fired up a second projector to continue the movie while he changed the arc light on the first one and loaded another reel. This back-and-forth continued for the duration of the film.

Although their commercial uses were limited by our nation’s then-puny electrical grid, and they were surpassed by newer means of illumination, arc lights were in use for years and remain incredibly simple to make at home: obtain two carbon rods, about the diameter of a pencil, by taking a hacksaw to a couple of D-size batteries. Run household alternating current through them, touch the ends together and slowly pull them apart, creating a loud, sizzling spark that would be right at home in Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory or somewhere along the Green Mile.

Safety precautions had to be taken, of course—I connected the wires to the rods with black electrical tape, and drilled holes in opposite sides of a clay flower pot to keep the rods parallel to each other as I pulled them apart bare-handed. Sunscreen might have been helpful, given the massive amount of ultraviolet light being emitted, but I’d be hungry for dinner before my exposure reached the sunburn stage.

I have a vivid memory of the first time I plugged in the contraption and slowly separated the rods—the deep hum, the blinding light, the smell of the carbon being vaporized. In professional use, the rods would be “self-regulated” by springs or solenoids that would maintain a proper distance between them as they diminished in length: too close or too far apart, and there would be no spark. I might have worn cheap sunglasses, although a welder’s mask would have been more appropriate. My parents, somehow, let me do this in the garage, maybe believing its dirt floor would ground me against all misfortune.

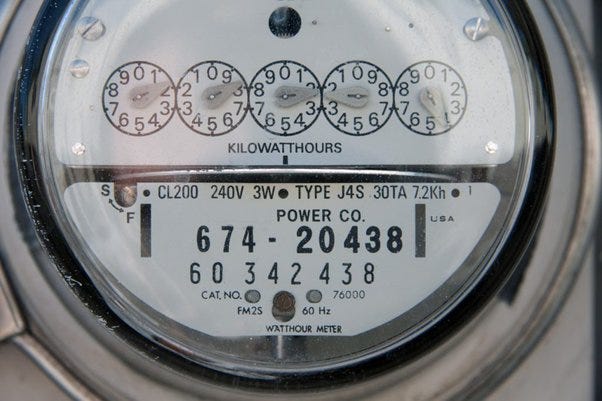

While our garage was being lit up like a nuclear test site one day, I walked over to the electrical meter on the side of the house. It held a flat, circular disc that tracked our home’s energy use in “kilowatthours” across five small analog clock faces. Normally, the movements of the disc and the clock faces were almost imperceptible.

When the arc light was doing its thing, they would spin like pinwheels.

Was our electric bill a little high that month? We were kids, and were not privy to that grownup stuff. But I’m grateful for parents who supported our curiosity, no matter the cost—as long as no one went blind, got electrocuted, or burned down the garage.

© 2022 David Potorti

Wow.

Glad you didn't look at the arc directly for too long. Or accidentally electrocute yourself. Wow.

Sounds like the experiment was a success though. Good idea with the flower pot.

Tangentially related- in art school a kid a year behind me was arc welding with oxy acetylene goggles on and I stopped him and told him to get an arc welding helmet instead. Upperclassmen were laughing and when I asked them why they didn't tell him to protect himself they told me he needed to learn a lesson.

Lots of macho posturing- not really the same as popular science, but maybe a cousin.

Lovely story of tolerant, supportive parents and your wayward, wonder-filled childhood.